Labelled

Every human on the planet is unique. Each of us represents a combination of biology, psychology and life experiences that have never occurred before, and will never occur again. While you might follow in the footsteps of others and have much in common with those around you, you are not the same as anyone else. You are unique.

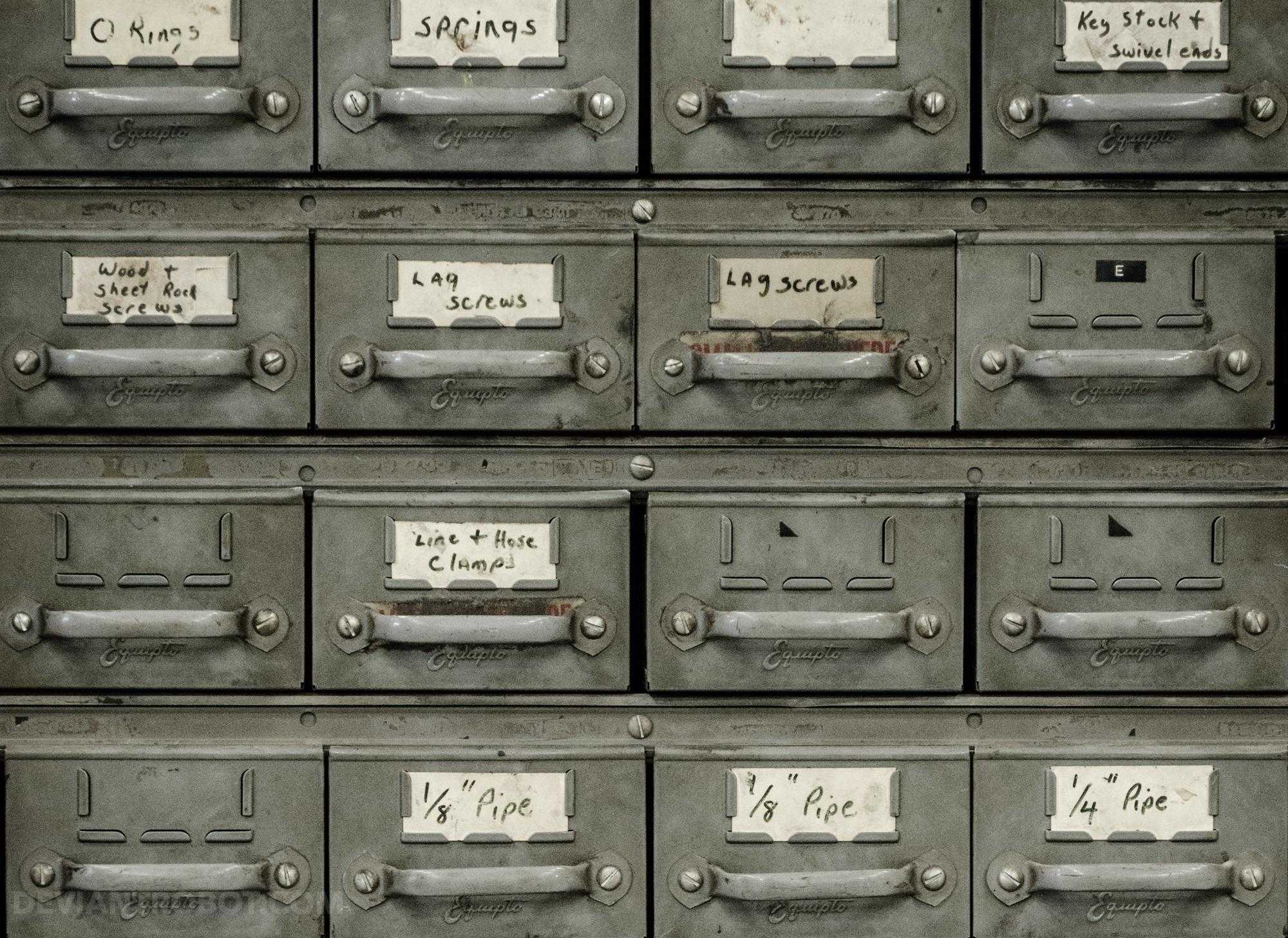

From the moment you were born (and possibly even before), many of the characteristics that combine to make you unique were being labelled. It’s nothing personal; it’s just that to understand who you are, we need to describe you. To do that, we use language, and language is about giving labels to ideas.

The labels we use to describe ourselves, each other, and indeed everything else in the world are not perfect. A lot of nuance gets lost behind labels, as we tend to gave similar characteristics broad, general terms. Unfortunately, labels that are more specific, specialised and nuanced are also likely to be less familiar or well understood. Labels that are less familiar or well understood represent a problem as labels, and indeed words only have value if their meaning comes with a shared understanding. Specialised terms only survive within special interest groups, and can’t easily be used outside of those groups. For example, medical terminology freely used amongst doctors might as well be a foreign language to those without medical training. As a result, we are much more likely to use broad and general terms.

“Do not free a camel of the burden of his hump; you may be freeing him from being a camel.”

Only 0.06% of the population of America has a different eye colour for each eye; as a result, it is unlikely that most Americans will know the term Heterochromia Iridum, which describes the phenomenon. They simply would never have reason to know it. Similarly, it’s likely that were it to be more common, it would have a less cumbersome name, as frequent use smooths off rough linguistic edges. Most people no longer will say “God be with you”, instead they simply say Goodbye which in fact is a contraction of “God be with you”. Heterochromia Iridum might end up as “Hetrum” or something similar were it to be more commonplace. Even language used to describe the more commonplace might see more descriptive terms undermined by more familiar ones. A ‘Myoclonic Jerk’ is arguably a more accurate description, but people most will probably always call it a hiccup. Similarly, Alopecia Areata might be the more precise term for a specific case, but people would describe someone with the condition as merely ‘going bald’. Despite baldness being a symptom of a wide range of conditions for which we likely have better, if less well known, labels.

The collection of commonly understood labels that represent human language, flawed as it is, has still been amazingly effective. Communication has been one of the fundamental components in the flourishing of human civilisation. While language is too imperfect a tool in the hyper-specialised case of describing a specific human; it works remarkably well for most of what humans might seek to communicate to each other.

It ain't what they call you, it's what you answer to.

The usefulness of general descriptions

Humans spend the vast majority of their time operating at a level of detail that need not be very specific. Given a random population of a hundred people, it would be possible to describe a single individual within that group with just a handful of terms; even if those terms were not very specific. For example, specifying a person in our random population of a hounded people as being a tall male with pale-skin and reddish hair would significantly narrow the field, and perhaps even be enough to identify a single individual.

If I was to say I once met an 18 to 24-year-old colour-blind English woman, who could not roll her tongue, had red hair and was left-handed, it might not sound so remarkable. Whilst some of those traits slightly unusual, they are not especially uncommon. However, despite a global population of around 7.7 billion people; statistically, there are likely only five such women in the world that would match that description.

People are too complicated to have simple labels.

The map is not the territory

For most of what we functionally require of labels, we seem to be well served. However, it’s important not to mistake the label for the thing it is describing.

Some labels we might not want, “criminal”, “untrustworthy”, “unreliable”. Labels might have a hidden context; we might describe a man as “short” when he plays basketball and “tall” if he was to become a jockey. Sometimes a label is just misunderstood or just plain wrong. Labels might make our life more difficult, “immigrant” or “minority”, “weird” and at other times they might help save our lives; “asthmatic” or “diabetic”. However, no matter what the labels used to describe you, they will always be imperfect and will never be the truth of who you are.